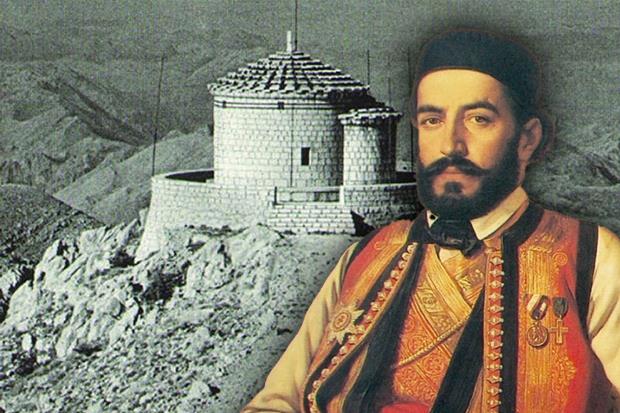

The main topic of the article is the history, significance, and fate of Njegoš’s chapel on Lovćen, dedicated to Saint Peter of Cetinje. The chapel was originally built in the 19th century by Njegoš’s order as his burial endowment, but he was not buried there due to wartime circumstances. Throughout history, the chapel was repeatedly destroyed and rebuilt, including shelling by Austro-Hungarian forces during World War I and demolition after World War II for political reasons. Later, a mausoleum by Ivan Meštrović was built on the chapel’s site, which sparked controversy as it did not respect Njegoš’s vow. There is a strong desire and mission to restore the chapel in its original form, designed by architect Nikolai Krasnov, as a symbol of Montenegrin culture, faith, and history. The topic is presented as an important part of national identity and spiritual heritage of Montenegro, emphasizing respect for Njegoš’s vow and the chapel’s significance as a spiritual and historical symbol.

Political Perspectives:

Left: Left-leaning sources emphasize the cultural and historical significance of Njegoš’s chapel as a symbol of Montenegrin identity and heritage. They highlight the political motivations behind the destruction of the chapel, especially during the communist era, framing it as an attack on religious and national traditions. The narrative often stresses the importance of restoring the chapel to honor Njegoš’s original vow and preserve the spiritual legacy of Montenegro.

Center: Center-leaning sources present a balanced historical overview of the chapel’s construction, destruction, and restoration efforts. They acknowledge the complex political and historical contexts that led to the chapel’s multiple destructions, including wartime damage and ideological conflicts. The focus is on the architectural and cultural value of the chapel and the ongoing debates about how best to preserve this heritage while respecting historical facts.

Right: Right-leaning sources tend to emphasize the chapel as a sacred national and religious symbol, often linking it to Serbian Orthodox heritage and Njegoš’s role as a national poet and spiritual leader. They criticize the communist and foreign powers for desecrating the chapel and stress the need to fully restore it according to Njegoš’s wishes. The narrative may also include a patriotic tone, highlighting the chapel as a symbol of resistance and national pride.